Cape Dory 36 - A Survey

by Fraser and Jean Fraser-Harris

Reprinted with permission from Nautical Quarterly No.

18, Summer 1982

Copyright 1982 Nautical Quarterly, Inc.:

All Rights Reserved under Pan American and universal copyright conventions.

Reproduction without permission is prohibited.

In the same year that I retired from the Navy to turn professional

yachtsman, a much younger man embarked upon a boatbuilding venture.

Andrew Vavolotis, sailor and professional engineer, had learned much

of his boatbuilding skill with the Boston Whaler Company and determined

to try it on his own in 1962. He is still at it, and most successfully.

Construction of the first Cape Dory, a 15-footer, began in his garage

in Brockton, Massachusetts. Soon he moved to a shop in West Bridgewater

where he built fiberglass boats by day and drove the truck that delivered

them at night. Three companies are now under his private ownership

and personal direction-Cape Dory Yachts, Spartan Hardware, and Cape

Dory Charters, Inc. Each one interlocks in this story of his 36' cutter.

The development of Cape Dory Yachts is a Horatio Alger story. Because

it was and still is a private company in the process of growing, decisions

had to be very carefully made; there was no room for failure. Steps

up the ladder from the first 15-footer to this 36' cruising vessel,

launched three years ago, took fifteen of the eighteen elapsed years

since the start of the company. From the 19' Typhoon daysailer to the

projected 45' ocean cruiser now in design, the concept of Andy Vavolotis's

boats has changed little save in size and the requirement of ocean-going

ability. They have all been full-keeled, easily-handled vessels with

emphasis upon rugged construction, simplicity and safety.

Six years ago, Andy Vavolotis started the related company, Spartan.

As his yachts grew larger, more specialized hardware began to be required;

changes in design meant seeking out new suppliers; spar and rigging

contracts had to be changed, and essential quality control could not

be exercised over someone else's manufacturing.

Spartan was born of this

need and now occupies a part of the East Taunton Factory where almost

all of the hardware, spars and rigging components for Cape Dory Yachts

are manufactured. Not only has this contributed to the quality of Cape

Dory's own yachts, but also directly to revenue since many Spartan

products, such as its well-designed bronze seacocks, are sold to other

manufacturers. This associated company now stands upon its own feet.

Spartan was born of this

need and now occupies a part of the East Taunton Factory where almost

all of the hardware, spars and rigging components for Cape Dory Yachts

are manufactured. Not only has this contributed to the quality of Cape

Dory's own yachts, but also directly to revenue since many Spartan

products, such as its well-designed bronze seacocks, are sold to other

manufacturers. This associated company now stands upon its own feet.

The Cape Dory Charter Company, moving into its third season, is another

smart move. Unlike most charter companies which practice a variety

of lease-back and similar tax-avoidance schemes to stock their fleets,

this one owns its own boats, assigned new to a small fleet operating

out of Marion, Massachusetts and, during the winter months, Clearwater,

Florida. This organization serves two excellent purposes: it is a fine

testing ground for the boats and, secondly, it enables a prospective

purchaser to spend a week in the yacht of his choice before making

a decision to purchase. If he buys, his charter fee is returned; if

he doesn't, at least he's had a sailing holiday. This seems to us a

neat way to sell a boat, and an even better way to buy one.

To return to our subject, the Cape Dory 36, it is obvious that the

faithful relationship with Carl Alberg that this company has maintained

over the years is in large measure responsible for the success of this

boat. In the world of cruising yachtsmen, no designer is more respected.

Carl Alberg is a man of the old school, yet his designs remain consistently

contemporary. Those that have been launched by good builders have become

sought-after classics. Alberg, resting on well-earned laurels in semi-retirement,

nevertheless still works closely with Cape Dory Yachts. The 36 is a

joint product of his design skill and the practical specifications

provided by Vavolotis and his team.

Finally, as engineer and chief of quality control at the factory,

whom do we find but OSTAR competitor Jim Kyle, class winner in the

Bermuda singlehander. Like all good sailors, he is a careful fellow,

and he greeted us with some suspicion. Not until we had exchanged a

variety of nautical experiences over lunch did he pay us a somewhat

backhanded compliment; he was "happy to find we weren't writers,

but seemed to know what we were talking about!"

Jim Kyle's quality control is far more than two words in his title;

there is an effective team, with each man an authority in his own field.

Together they operate with the aid of lengthy checklists, backed up

by in-house mechanical and chemical test facilities. While not wishing

to extol unduly the virtues of singlehanders (some people think they're

crazy), one must admit that their practical survival training when

coupled to engineering and design degrees imbues confidence in the

quality they control. Kyle is not a man to countenance poor practice

in the production of an ocean-cruising yacht.

And so to the construction of the 36.

The hull is laid up in a single mold mounted on a rotating frame

to permit easy access and near-horizontal surfaces for best resin

distribution. To make possible the construction of an integral inbound

lip for attachment of the deck/coachroof molding, a separate and

detachable flange section is bolted onto the mold. The lip is laid

up inside this section of the mold, which is then removed to permit

extraction of the completed hull.

The layup is conventional alternate

layers of hand-laid mat and roving, tapering from a total of 15 layers

at the keel down to 10 at the topside flange. A chopper gun is, however,

used to set the first layer behind the gelcoat on the hulls and to

a greater extent in deck laminates; but to minimize the possibility

of gelcoat stress cracks at coachroof corners and cockpit coamings,

unidirectional glass strand is laid in as reinforcement.

The layup is conventional alternate

layers of hand-laid mat and roving, tapering from a total of 15 layers

at the keel down to 10 at the topside flange. A chopper gun is, however,

used to set the first layer behind the gelcoat on the hulls and to

a greater extent in deck laminates; but to minimize the possibility

of gelcoat stress cracks at coachroof corners and cockpit coamings,

unidirectional glass strand is laid in as reinforcement.

The molding shops are carefully controlled for both temperature

and air purity by powerful fan/filters; the bulk resin is stored

in tanks and piped from them to the working areas by means of a central

resin distribution system where it is subject to frequent chemical

check. We were particularly impressed by the care devoted to the

design and construction of the rudder. The 1 1/2" stainless

stock bar is curved inside the molding, following the shape of the

cutout for the propeller. The stock bar is solidly glassed into a

prepared trough. At the base of the rudder a cast bronze web with

gudgeon tube accepts the pintle pin on the heel casting which is

also glassed into the rudder molding. Next, the half shells are tilled

with reinforced polyester compound, glassed together and carefully

sealed with fiberglass tape.

One of Jim Kyle's phobias is the use of welding in a marine environment,

either for stainless steel or aluminum. He has a valid point, for

the molecular disturbance will create the possibility of small areas

of metal in way of the weldings becoming vulnerable to corrosion.

For this reason he has avoided the use of welding where possible

in the manufacture of hull hardware and spars. An exception is the

heavy steel bracket which holds the steering sheaves and stops. This

is not stainless, but mild steel, and is heavily paint-dipped for

protection.

Spartan spar construction shows similar attention to practical detail.

At the spreader attachment points, for instance, the compression

tubes do not pass through the mast where stress can be transferred

from one to the other. Instead, they are carefully placed inside

the mast extrusion, thus confining the load to the walls of the mast.

The gooseneck fitting is simple and strong, again not welded but

fitted and screwed into the boom. In the unlikely event of failure,

a spare can be easily substituted. This philosophy of practical simplicity

is evident throughout the construction and outfitting of this yacht.

Chainplate construction is again unusual, but has both logical and

sound engineering precedent. To remove as much steel as possible,

a change has been made here. In earlier hulls a steel web was used,

but after hull No. 71, now on the line, it is replaced by an aluminum

angle bar. Some three feet in length, this plate is glassed with

uni-directional strands into the hull under the lip. It is positioned

during the hull layup process, and the first layers of unidirectional

are led behind the last layers of roving, thus interlocking the whole

structure. Finally, the wide deck plates, well bedded, are bolted

through the deck/hull flange and aluminum bar.

This system eliminates any possible movement between chainplate

and deck, so often a source of leaks. Since the aluminum plate is

molded into the hull, which is also reinforced by the unidirectional

glass for a considerable distance down to its thicker cross-section,

the loads are evenly distributed and well spread.

Bulkheads and floors are well bonded, glasswork tidy and joinery

neat.

As we approached the end of the production line another unusual but

simple alternative solution to a major problem in fiberglass yacht

construction was found. The usual practice in developing a strong hull/deck

joint is to rely upon a heavy mastic for sealing while giving strength

by installing stainless-steel bolts at 4"-5" centers on a

lip of about 2". Cape Dory's system attempts to keep the mechanical

strength of bolts but also to eliminate leaks by reducing, insofar

as practical, the number of through-deck fastenings. Thus they extend

the lip to some 3 1/4" and use a semi-rigid polyester bonding

compound with considerable sheer strength. The joint is held tight

by fasteners during the bonding process. After curing, these are replaced

by 1/2" stainless bolts at 12" centers. The latter are then

covered by a well-bedded teak toerail whose screws pass through both

deck and hull flange for additional strength. A teak rubrail is then

screwed into the hull molding. It is significant that the thickness

of the hull laminate at the flange is some 3/8", substantial in

a vessel of this size.

Turning to electrical and engineering systems, we will comment on

what we were able to observe along the production line. A separate

lightning protection system consists of direct bonding of mast and

shrouds to an external grounding plate. Thus, the jolt of a lightning

strike is kept away from both electrical equipment and the through-hull

bonding system, which is an entirely separate web connecting all through-hulls

and tank groundings.

An integral 36-gallon fiberglass holding tank is glassed into the

hull molding above the ballast. The 43-gallon fiberglass fuel tank

and four molded polyethylene water tanks with a total capacity of 110

gallons are well secured in molded saddles. A 6-gallon hot water heater

installed in the port locker is standard equipment. Two heavy-duty

12-volt batteries, also carried in this locker, have properly color-coded

leads, and are well stowed in ventilated plastic containers and strapped

down, but readily accessible for servicing.

Electrical circuitry is efficiently installed, with 110- and 12-volt

breaker panels well set up. Polarity alarm, battery test and red circuit

indicator lights are all standard equipment.

There is hot water and a shower, but refrigeration must be an owner

option. The 110 circuits are supplied for water heater and outlets

only, but three additional plugs are available on the breaker panel

for battery charger or other options. On the 12-volt panel a breaker

is provided for the radio and for the instruments; again, two spares

are available for extra circuitry such as stereo or Loran systems.

The installation of the Perkins 4-108 diesel allows ease of maintenance,

the compartment is nicely soundproofed, and a drip tray is provided.

Two filters on the fuel line, one a water separator, are standard.

Engine bearers are steel-cored fiberglass strongly bonded to the hull

with the load well spread. Noteworthy is the prop-log stuffing box,

a "Spartan special" designed so that it can be adjusted with

the tap of a hammer instead of the usual battle of finding a wrench

to fit-cunning!

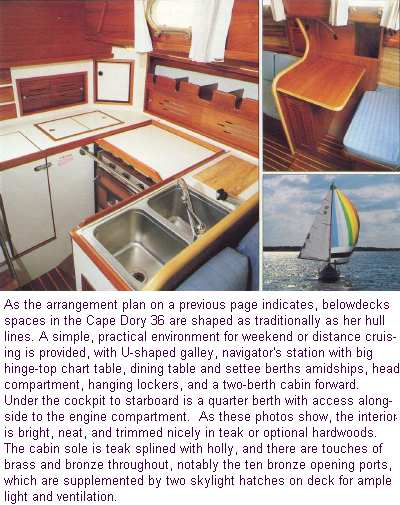

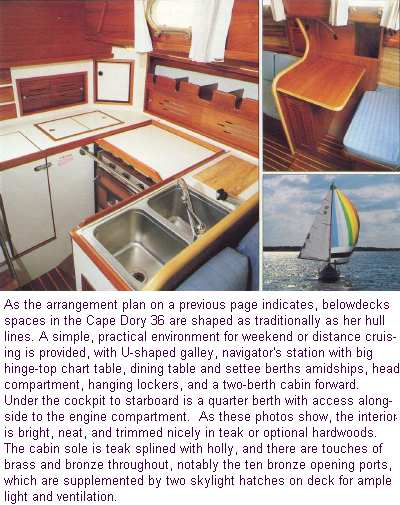

The interior is light, bright and airy. Perhaps the most outstanding

feature is the warmth and luxury of the polished bronze portlights

and hardware supplied by Spartan. These are a Cape Dory trademark,

but they are not just decorative; the portlights are very tough hardware

and carry heavy safety glass which has plenty of strength and will

not craze with age.

In the old pre-war Navy days, it was said that one of the reasons

there was so much brass around was that it gave the crew something

to do when they were not fighting. Maybe polishing all these beautiful

fittings will keep the crew from fighting. Providing, of course, that

they take turns!

In the standard V-berth (with filler) forecabin there is 4" foam

upholstery, ample headroom and satisfactory dressing space. The head

is a glass molding easy to keep clean and very adequate in space and

arrangement. The basin, shower and ice box drain into a bilge sump.

This we don't much like, since emptying the bathwater into the basement

is not good housekeeping. Bilge sumps are difficult to clean and get

very "ucky" with old soap, - spilt milk, etc. A shower sump

with automatic overboard discharge and a small hand pump for removal

of icebox sediment into a sink-drain connection would be preferable.

The galley is good news, with plenty

of working, drawer and stowage space. Jean again complained that she

found no allowance for her toes under the counters. Like gimballed

tables, these spaces under galley furniture, which make standing at

work so much more comfortable, seem to be rare. We also felt that in

a 36' cruising vessel an alternative refrigeration system might be

taken into account, and that the 2 1/2" insulation of the box

is marginal. In tropical conditions, nothing under 3" is really

effective. The gimballed 3-burner stove with oven is available with

either alcohol or gas fuel to ABYC-approved systems.

The galley is good news, with plenty

of working, drawer and stowage space. Jean again complained that she

found no allowance for her toes under the counters. Like gimballed

tables, these spaces under galley furniture, which make standing at

work so much more comfortable, seem to be rare. We also felt that in

a 36' cruising vessel an alternative refrigeration system might be

taken into account, and that the 2 1/2" insulation of the box

is marginal. In tropical conditions, nothing under 3" is really

effective. The gimballed 3-burner stove with oven is available with

either alcohol or gas fuel to ABYC-approved systems.

Despite these quibbles, our enthusiasm for the general standard of

the interior remains: 6'4" headroom in the saloon with grabrails

both sides, in addition to drip rails under the ports. Comfortable

settees with sloped backs. Solid drop table with shelves behind on

the bulkhead. (A pedestal table is an available option.)

One touch much appreciated by old cruising hands is the thought applied

to the Cape Dory 36 "Owner's Manual." This includes a commissioning

check list, simple instructions on all systems, including pipe and

wiring diagrams, and even a list of addresses for all subcontractors

together with part numbers-everything from sheet blocks to light bulbs.

And so on deck for the sea trial. An inspection of this boat's rigging

inspires confidence-with standing rigging 1 x 19 Seabrite stainless

to open Merriman turnbuckles and toggles, and halyards all rope in

the form of pre-stretched Marlow braid. Spreaders are very wide and

shroud leads well out to give both good mast support and clear space

for movement fore and aft on deck. Double-rail stainless pulpit and

stemrail, double guardrails, small cockpit well with ample seats, and

half deck with good sill height to companionway-all contribute to a

feeling of security in ocean sailing and the assurance of comfort and

deck space for weekend cruising.

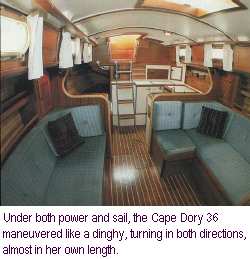

The boomed staysail and mainsheets clear of the cockpit, with provision

for double jiffy reefing, seven Lewmar winches with two-speed #40 self-tailing

Lewmar primaries, and light and sensitive wheel, made control and sail

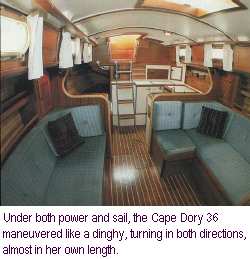

handling a pleasure. Under both power and sail the yacht maneuvered

like a dinghy, turning in both directions almost in her own length.

Under power,

the Cape Dory 36 exceeds seven knots at cruising rpm and moves without

fuss. Noise level is low in the cockpit and below. Under sail, with

wind speeds between fifteen and eighteen knots, we carried 100% genoa,

staysail and full main. The boat is stiff, but control was finger light

on all headings. There was no compass on board so that accurate tack

angles could not be obtained, but she drove well to windward with staysail

slightly eased to provide a good slot. Under main and staysail only,

tacking without sheet handling was quick and acceleration was good.

We did not encounter rough water this trip, but in the slight chop

there was little movement.

Under power,

the Cape Dory 36 exceeds seven knots at cruising rpm and moves without

fuss. Noise level is low in the cockpit and below. Under sail, with

wind speeds between fifteen and eighteen knots, we carried 100% genoa,

staysail and full main. The boat is stiff, but control was finger light

on all headings. There was no compass on board so that accurate tack

angles could not be obtained, but she drove well to windward with staysail

slightly eased to provide a good slot. Under main and staysail only,

tacking without sheet handling was quick and acceleration was good.

We did not encounter rough water this trip, but in the slight chop

there was little movement.

During the sailing trial we were accompanied by the new owners, who

had just completed sailing school. This was their first "big" boat

and their first time out in her. After some initial apprehension they

began to share our confidence. When we departed we were convinced that

they had chosen well; they would have little difficulty mastering this

wholesome thoroughbred and were destined to enjoy some very rewarding

sailing.

Altogether, we found the Cape Dory 36 an excellent vessel for the

cruising sailor - comfortable, simple, seamanlike. She should be equally

at home on a social weekend or an ocean crossing.

Specifications:

| LOA: |

36' 1 1/2" |

| LWL: |

27' |

| Beam: |

10' 8" |

| Draft: |

5' |

| Sail Area: |

622 sq. ft. |

| Ballast: |

6050 pounds |

| Displacement: |

16,100 pounds |

| Fuel: |

42 gallons |

| Water: |

130 gallons |

| Power: |

Perkins 50-HP 4-108 diesel |

| Spars: |

Aluminum finished with Awlgrip |

| Designer: |

Carl Alberg |

| Builder: |

Cape Dory Yachts,

160 Middleboro Avenue,

East Taunton, MA 02718 |

Page last updated February 7, 2000.

Article and illustrations scanned and clearance

obtained by Ken Coit.,

who says:

"We have a number of people to thank for gaining

the right to publish the article on the web site:

Fraser and Jean Fraser-Harris, of Bristol, UK,

the authors.

Joseph P. Gribbins, the Editor of Nautical Quarterly

at that time and now with Mystic Seaport did a bit of research

on the article for us.

Dave Perry, formerly the Sales Manager for Cape

Dory and now with Robinhood Marine, who identified Windsong, the

individuals in the photos, the fact that the photos were from a

Cape Dory brochure, and that Windsong was in the fleet of Cape

Dory Charters.

Dave Perry tells us that the crew on the photo

shoot were all Cape Dory employees and had signed releases: Lou

Scott, Purchasing Manager at CDY is at the helm, Ed Reily, Quality

Control inspector, on port side and Hunter Scott, Assistant Production

Manager, is starboard.

Esther Pope, Editorial Assistant at Soundings,

helped get the ball rolling with an address for Fraser and Jean

Fraser-Harris in the UK and the lead to Joe Gribbins at Mystic

Seaport.

And, there were others who responded to my direct

inquiries or broadcasts for assistance with clues about Windsong."